924

Lectures Watched

Since January 1, 2014

Since January 1, 2014

- A History of the World since 1300 (68)

- History of Rock, 1970-Present (50)

- A Brief History of Humankind (48)

- Chinese Thought: Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science (35)

- The Modern World: Global History since 1760 (35)

- The Bible's Prehistory, Purpose, and Political Future (28)

- Introduction aux éthiques philosophiques (27)

- Jesus in Scripture and Tradition (25)

- Roman Architecture (25)

- Sexing the Canvas: Art and Gender (23)

- Descubriendo la pintura europea de 1400 a 1800 (22)

- Introduction aux droits de l'homme (19)

- Buddhism and Modern Psychology (18)

- Calvin: Histoire et réception d'une Réforme (17)

- The Ancient Greeks (16)

- À la découverte du théâtre classique français (15)

- The French Revolution (15)

- Letters of the Apostle Paul (14)

- Key Constitutional Concepts and Supreme Court Cases (14)

- Christianisme et philosophie dans l'Antiquité (14)

- Egiptología (12)

- Western Music History through Performance (10)

- The Rise of Superheroes and Their Impact On Pop Culture (9)

- The Great War and Modern Philosophy (9)

- Alexander the Great (9)

- Greek and Roman Mythology (9)

- Human Evolution: Past and Future (9)

- Phenomenology and the Conscious Mind (9)

- Masterpieces of World Literature (8)

- Villes africaines: la planification urbaine (8)

- Greeks at War: Homer at Troy (7)

- Pensamiento Científico (7)

- MongoDB for Node.js Developers (7)

- Fundamentos de la escritura en español (7)

- Introduction to Psychology (7)

- Programming Mobile Applications for Android (7)

- The Rooseveltian Century (6)

- Karl der Große - Pater Europae (6)

- Fake News, Facts, and Alternative Facts (6)

- Reason and Persuasion Through Plato's Dialogues (6)

- The Emergence of the Modern Middle East (6)

- A Beginner's Guide to Irrational Behavior (6)

- Lingua e cultura italiana: avanzata (6)

- L'avenir de la décision : connaître et agir en complexité (5)

- Understanding Einstein: The Special Theory of Relativity (5)

- Dinosaur Paleobiology (5)

- Exploring Beethoven's Piano Sonatas (5)

- War for the Greater Middle East (4)

- Emergence of Life (4)

- Introduction to Public Speaking (4)

- The Kennedy Half Century (4)

- Problèmes métaphysiques à l'épreuve de la politique, 1943-1968 (4)

- Designing Cities (4)

- Western Civilization: Ancient and Medieval Europe (3)

- Paleontology: Early Vertebrate Evolution (3)

- Orientierung Geschichte (3)

- Moons of Our Solar System (3)

- Introduction à la philosophie de Friedrich Nietzsche (3)

- Devenir entrepreneur du changement (3)

- La Commedia di Dante (3)

- History of Rock and Roll, Part One (3)

- Formation of the Universe, Solar System, Earth and Life (3)

- Initiation à la programmation en Java (3)

- La visione del mondo della Relatività e della Meccanica Quantistica (3)

- The Music of the Beatles (3)

- Analyzing the Universe (3)

- Découvrir l'anthropologie (3)

- Postwar Abstract Painting (3)

- The Science of Religion (2)

- La Philanthropie : Comprendre et Agir (2)

- Highlights of Modern Astronomy (2)

- Materials Science: 10 Things Every Engineer Should Know (2)

- The Changing Landscape of Ancient Rome (2)

- Lingua e letteratura in italiano (2)

- Gestion des aires protégées en Afrique (2)

- Géopolitique de l'Europe (2)

- Introduction à la programmation en C++ (2)

- Découvrir la science politique (2)

- Our Earth: Its Climate, History, and Processes (2)

- The European Discovery of China (2)

- Understanding Russians: Contexts of Intercultural Communication (2)

- Philosophy and the Sciences (2)

- Søren Kierkegaard: Subjectivity, Irony and the Crisis of Modernity (2)

- The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem (2)

- The Science of Gastronomy (2)

- Galaxies and Cosmology (2)

- Introduction to Classical Music (2)

- Art History for Artists, Animators and Gamers (2)

- L'art des structures 1 : Câbles et arcs (2)

- Russian History: from Lenin to Putin (2)

- The World of Wine (1)

- Wine Tasting: Sensory Techniques for Wine Analysis (1)

- William Wordsworth: Poetry, People and Place (1)

- The Talmud: A Methodological Introduction (1)

- Switzerland in Europe (1)

- The World of the String Quartet (1)

- Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1)

- El Mediterráneo del Renacimiento a la Ilustración (1)

- Science of Exercise (1)

- Социокультурные аспекты социальной робототехники (1)

- Russian History: from Lenin to Putin (1)

- The Rise of China (1)

- The Renaissance and Baroque City (1)

- Visualizing Postwar Tokyo (1)

- In the Night Sky: Orion (1)

- Oriental Beliefs: Between Reason and Traditions (1)

- The Biology of Music (1)

- Mountains 101 (1)

- Moral Foundations of Politics (1)

- Mobilité et urbanisme (1)

- Introduction to Mathematical Thinking (1)

- Making Sense of News (1)

- Magic in the Middle Ages (1)

- Introduction to Italian Opera (1)

- Intellectual Humility (1)

- The Computing Technology Inside Your Smartphone (1)

- Human Origins (1)

- Miracles of Human Language (1)

- From Goddard to Apollo: The History of Rockets (1)

- Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales (1)

- Handel’s Messiah and Baroque Oratorio (1)

- Theater and Globalization (1)

- Gestion et Politique de l'eau (1)

- Une introduction à la géographicité (1)

- Frontières en tous genres (1)

- Créer et développer une startup technologique (1)

- Découvrir le marketing (1)

- Escribir para Convencer (1)

- Anthropology of Current World Issues (1)

- Poetry in America: Whitman (1)

- Introducción a la genética y la evolución (1)

- Shakespeare: On the Page and in Performance (1)

- The Civil War and Reconstruction (1)

- Dinosaur Ecosystems (1)

- Développement durable (1)

- Vital Signs: Understanding What the Body Is Telling Us (1)

- Imagining Other Earths (1)

- Learning How to Learn (1)

- Miracles of Human Language: An Introduction to Linguistics (1)

- Web Intelligence and Big Data (1)

- Andy Warhol (1)

- Understanding the Brain: The Neurobiology of Everyday Life (1)

- Practicing Tolerance in a Religious Society (1)

- Subsistence Marketplaces (1)

- Physique générale - mécanique (1)

- Exercise Physiology: Understanding the Athlete Within (1)

- Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy (1)

- What Managers Can Learn from Great Philosophers (1)

- A la recherche du Grand Paris (1)

- The New Nordic Diet (1)

- A New History for a New China, 1700-2000 (1)

- The Magna Carta and its Legacy (1)

- The Age of Jefferson (1)

- History and Future of Higher Education (1)

- Éléments de Géomatique (1)

- 21st Century American Foreign Policy (1)

- The Law of the European Union (1)

- Design: Creation of Artifacts in Society (1)

- Introduction to Data Science (1)

- Configuring the World (1)

- From the Big Bang to Dark Energy (1)

- Animal Behaviour (1)

- Programming Mobile Services for Android Handheld Systems (1)

- The American South: Its Stories, Music, and Art (1)

- Care of Elders with Alzheimer's Disease (1)

- Contagious: How Things Catch On (1)

- Constitutional Law - The Structure of Government (1)

- Narratives of Nonviolence in the American Civil Rights Movement (1)

- Christianity: From Persecuted Faith to Global Religion (200-1650) (1)

- Age of Cathedrals (1)

- Controversies of British Imperialism (1)

- Big History: From the Big Bang until Today (1)

- Bemerkenswerte Menschen (1)

- The Art of Poetry (1)

- Superpowers of the Ancient World: the Near East (1)

- America Through Foreign Eyes (1)

- Advertising and Society (1)

Hundreds of free, self-paced university courses available:

my recommendations here

my recommendations here

Peruse my collection of 275

influential people of the past.

influential people of the past.

View My Class Notes via:

Receive My Class Notes via E-Mail:

Contact Me via E-Mail:

edward [at] tanguay.info

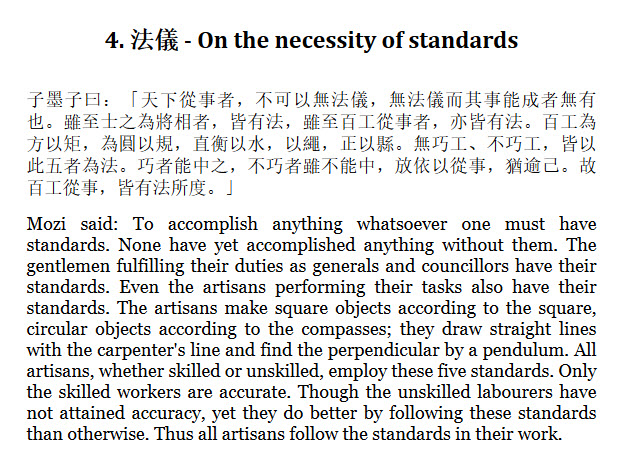

Notes on video lecture:

Mozi and Materialist State Consequentialism

Notes taken by Edward Tanguay on March 28, 2017 (go to class or lectures)

Choose from these words to fill the blanks below:

salary, ethicist, hot, wealth, repetitive, chaos, physical, respect, three, died, literary, rewards, pragmatic, maximize, benefit, Mohism, consequentialism, self, Mencius, nature, argument, consequences, theme, devotion, elaborate, carpenter, Confucianism, Confucius, benefits, harness, desires, Analects, psychology, classical, Hanfeizi, starving, meager, GDP, good, rationalists, crafts, cells, reshaped, master, whom, mystical, material

•

Mozi (468-391 BCE)

•

the "zi" means

•

Mozi = Master Mo

•

Laozi = Master Lao

•

lived after (551-479 BCE)

•

lived before (390-310 BCE)

•

one of the principal interpreters of

•

The Mozi

•

expounds the philosophy of

•

structured much like the

•

collected after he

•

may have penned some of the chapters

•

disciples were organized more like an army

•

organized into

•

each of the cells had its own master

•

each cell could have sub-cells which had their own masters

•

after Mozi died, each of the Mozi lineages fought among themselves to determine who was the most orthodox one

•

there are three versions of the same chapters

•

each chapter has a , and a title that tells you what the chapter is about

•

chapters are reasonably well-argued argument

•

structured around themes in a coherent way

•

writing style

•

plodding and

•

how do we know x, this is how we know x

•

it's dry in English and it's dry in Chinese

•

it's bad classical Chinese style

•

the Daodejing is beautifully poetic

•

has a language

•

the Analects are also a very high level of achievement

•

the Mozi is dry

•

in the chapter, there is a defense of the style

•

that it is deliberate

•

they are

•

they want you to follow this rational

•

they don't want you to be distracted by fancy rhetoric

•

Mozi and his followers were -educated people

•

they are not coming from a hereditary elite

•

didn't learn Chinese at an early age

•

Mozi was probably a

•

uses many craft metaphors

•

one of his innovations was using these metaphors of and applying it to philosophy

•

very

•

doesn't seem to need for music or funerals

•

Mozian

•

the ethical thing to do is decided by weighing its

•

weigh the consequences of behavior x

•

these good things happen

•

these bad things happen

•

different types of consequentialism, vary on:

•

which types of consequentialism you want to

•

which perspective you are varying it from, i.e. consequences for

•

kinds of consequentialists

•

happy consequentialists

•

maximize happiness and well-being

•

this is vague

•

most contemporary consequentialists in the West

•

consequentialists

•

maximize Gross Domestic Product

•

anything that increases it is

•

anything that decreases it is bad

•

theistic consequentialists

•

anything that increases to diety is good

•

anything that decreases devotion to diety is bad

•

consequences for whom

•

the individual

•

the city

•

the state

•

combination

•

action x could maximize material for you personally, but not for the state

•

Mozi is a materialist, state consequentialist

•

the goal is to maximize material well-being for the state

•

well-being for him meant goods

•

food

•

shelter

•

believes that people are only motivated by motives

•

even if they talk about idealistic concepts

•

"If an official has a high-sounding title but a stipend, he can hardly inspire the confidence of the people."

•

the only thing that is going to motivate people to be part of your government is a proper

•

use money to motivate people and inspire

•

differences to Confucius

•

love of the Way

•

you can and should endure material privations in order to align yourself with the Way

•

even to death was a good if you had the Way

•

rejection of wu-wei as an ideal

•

Mozi is a rationalist

•

favors cold cognition

•

ethics is about thinking rationally in a cold way and in engaging in cognitive control

•

he's deeply suspicious of cognition

•

it will lead to

•

he feels this is what the problem was with the Warring States

•

Confucius

•

we are born rough

•

our hot cognition is going to lead to chaos

•

it needs to get by Confucian culture

•

the key is to transform our hot cognition into something beautiful

•

Laozi

•

our hot cognition has been messed up by society

•

if you're able to read, you are literate and part of the elite, and hence already too messed up

•

we have to repress these added that we have been taught, forget them, get rid of them, to get back to the hot cognition that we would have if we were in touch with our

•

Mozi

•

hot cognition is itself the problem

•

but you can't change it

•

what you can do is it with cold cognition, i.e. reasoning, to make it behave in ways that are rational

•

we won't change our basic motivation but will apply external systems of punishments and to get people to make certain choices

•

in this way using cost and analysis to engineer the kind of society and behavior that is more rational

•

you don't need to change your inborn , but be institutionalized exteriorly through reason

•

and we will rely on their rationality to understand the of the Mozian Way

Spelling Corrections:

personaly ⇒ personally

Ideas and Concepts:

Ancient Chinese philosophy texts with tedious writing styles via tonight's Ancient Chinese Philosophy class:

"Mozi (468-391 BCE) was the leader of a Chinese school-of-thought named Mohism. He lived after Confucius (551-479 BCE) and before Mencius (390-310 BCE). His disciples were organized more like an army, organized into cells, each of the cells had its own master, and each cell could have sub-cells which had their own masters.

Mozi and his followers came from a working class background, most probably carpenters, were not from the hereditary learned classes, and so didn't learn classical Chinese at an early age. Not having a learned background, they did not see much need for fancy music or funerals, and their writing was straight forward and pragmatic, each chapter an argument and structured around a theme in a coherent way. They did not want their readers to be distracted by fancy rhetoric or stylistic embellishments, and so the writing style is often plodding and repetitive, boring in English as it is in Chinese.

Where the Daodejing often reads beautifully poetic with its mystical language, and the Analects has a very high level of literary achievement, reading the Mozi is often tedious, more like reading a manual than any kind of sacred text. In the Hanfeizi chapter, there is a defense of this style, arguing that it is deliberate, that they are rationalists, and they want you to follow rational arguments."

"Mozi (468-391 BCE) was the leader of a Chinese school-of-thought named Mohism. He lived after Confucius (551-479 BCE) and before Mencius (390-310 BCE). His disciples were organized more like an army, organized into cells, each of the cells had its own master, and each cell could have sub-cells which had their own masters.

Mozi and his followers came from a working class background, most probably carpenters, were not from the hereditary learned classes, and so didn't learn classical Chinese at an early age. Not having a learned background, they did not see much need for fancy music or funerals, and their writing was straight forward and pragmatic, each chapter an argument and structured around a theme in a coherent way. They did not want their readers to be distracted by fancy rhetoric or stylistic embellishments, and so the writing style is often plodding and repetitive, boring in English as it is in Chinese.

Where the Daodejing often reads beautifully poetic with its mystical language, and the Analects has a very high level of literary achievement, reading the Mozi is often tedious, more like reading a manual than any kind of sacred text. In the Hanfeizi chapter, there is a defense of this style, arguing that it is deliberate, that they are rationalists, and they want you to follow rational arguments."

On Mozian consequentialism via tonight's Ancient Chinese Philosophy class:

"Mozi (468-391 BCE) was the leader of a Chinese school-of-thought named Mohism. The philosophy of this school was called Mozian consequentialism, which taught that the ethical thing to do is decided by weighing its consequences. So you weigh the consequences of behavior x and determine what good things happen and what bad things happen, and you choose the actions that maximize good consequences.

There are, of course, different types of consequentialism, depending on (1) what you think is good, (2) what you want to maximize, and (3) for whom you want to maximize it.

Many contemporary moral consequentialists in the West desire to maximize happiness and well-being, one problem with this approach being that how one defines happiness and well-being can be vague.

Other contemporary consequentialists want to maximize GDP, so anything that increases the Gross Domestic Product is good, and anything that decreases it is bad.

Theistic consequentialists believe that one should maximize devotion to their deity, so anything that increases devotion to their deity is good, while anything that decreases devotion to their diety is bad.

One must also consider for whom consequences should be maximized, e.g. for the individual, the city, or the state. In this way, you arrive at combinations of consequentialism, e.g. you may practice a consequentialism which believes that you should partake in action x, since it maximizes material wealth for you personally, but not for the state, or you may want to maximize average well-being for the society, but not selfishly for the individual.

Mozi himself was a materialist, state consequentialist. His goal was to maximize material well-being for the state and the society as a whole. Well-being for him meant physical goods, e.g. food, warmth, shelter and physical needs in general. He believed that people are motivated primarily by material motives. Even if they talked about idealistic concepts, what they wanted was food, warmth, shelter, and to have their physical needs fulfilled.

Practically, this meant e.g. paying government officials well, as Mozi wrote, 'If an official has a high-sounding title but a meager stipend, he can hardly inspire the confidence of the people. The only thing that is going to motivate people to be part of your government is a proper salary.'

Notice the stark difference between the consequentialism of Mozi and the teachings of Confucius, who taught love of the Way, that you can and should endure material privations in order to align yourself with the Way, even starving to death was a good if you were aligned with the Way. Not so for Mozi."

"Mozi (468-391 BCE) was the leader of a Chinese school-of-thought named Mohism. The philosophy of this school was called Mozian consequentialism, which taught that the ethical thing to do is decided by weighing its consequences. So you weigh the consequences of behavior x and determine what good things happen and what bad things happen, and you choose the actions that maximize good consequences.

There are, of course, different types of consequentialism, depending on (1) what you think is good, (2) what you want to maximize, and (3) for whom you want to maximize it.

Many contemporary moral consequentialists in the West desire to maximize happiness and well-being, one problem with this approach being that how one defines happiness and well-being can be vague.

Other contemporary consequentialists want to maximize GDP, so anything that increases the Gross Domestic Product is good, and anything that decreases it is bad.

Theistic consequentialists believe that one should maximize devotion to their deity, so anything that increases devotion to their deity is good, while anything that decreases devotion to their diety is bad.

One must also consider for whom consequences should be maximized, e.g. for the individual, the city, or the state. In this way, you arrive at combinations of consequentialism, e.g. you may practice a consequentialism which believes that you should partake in action x, since it maximizes material wealth for you personally, but not for the state, or you may want to maximize average well-being for the society, but not selfishly for the individual.

Mozi himself was a materialist, state consequentialist. His goal was to maximize material well-being for the state and the society as a whole. Well-being for him meant physical goods, e.g. food, warmth, shelter and physical needs in general. He believed that people are motivated primarily by material motives. Even if they talked about idealistic concepts, what they wanted was food, warmth, shelter, and to have their physical needs fulfilled.

Practically, this meant e.g. paying government officials well, as Mozi wrote, 'If an official has a high-sounding title but a meager stipend, he can hardly inspire the confidence of the people. The only thing that is going to motivate people to be part of your government is a proper salary.'

Notice the stark difference between the consequentialism of Mozi and the teachings of Confucius, who taught love of the Way, that you can and should endure material privations in order to align yourself with the Way, even starving to death was a good if you were aligned with the Way. Not so for Mozi."

The differences between Confucius, Laozi, and Mozi, via this afternoon's Ancient Chinese Philosophy class:

"For Confucius, we are born rough-hewn like a stone or piece of wood that needs to be shaped. Relying on our hot cognition (primitive emotional states) is going to lead to chaos and so we need to be reshaped by Confucian culture. The key is to transform our hot cognition into something beautiful.

For Laozi, our hot cognition has been messed up by society. If you're able to read, you are literate and part of the elite, and hence are already too messed up. We need to repress these added desires that we have been taught, forget them, get rid of them, and get back to the hot cognition that we would have if we were in touch with our nature and had never been corrupted by culture.

For Mozi, hot cognition is itself the problem. But you can't change it as Confucius thinks you can. What you can do is harness it with cold cognition (reasoning) to make it behave in ways that are more rational. We won't ever be able to change our basic motivations but we can apply external systems of punishments and rewards to get people to make certain choices, and in this way using cost and benefit analysis to engineer the kind of society and behavior that is more rational. And we will rely on people's rationality to understand the benefits of the Mozian Way."

"For Confucius, we are born rough-hewn like a stone or piece of wood that needs to be shaped. Relying on our hot cognition (primitive emotional states) is going to lead to chaos and so we need to be reshaped by Confucian culture. The key is to transform our hot cognition into something beautiful.

For Laozi, our hot cognition has been messed up by society. If you're able to read, you are literate and part of the elite, and hence are already too messed up. We need to repress these added desires that we have been taught, forget them, get rid of them, and get back to the hot cognition that we would have if we were in touch with our nature and had never been corrupted by culture.

For Mozi, hot cognition is itself the problem. But you can't change it as Confucius thinks you can. What you can do is harness it with cold cognition (reasoning) to make it behave in ways that are more rational. We won't ever be able to change our basic motivations but we can apply external systems of punishments and rewards to get people to make certain choices, and in this way using cost and benefit analysis to engineer the kind of society and behavior that is more rational. And we will rely on people's rationality to understand the benefits of the Mozian Way."